Kartchner Caverns State Park

Xanadu for Spelunkers

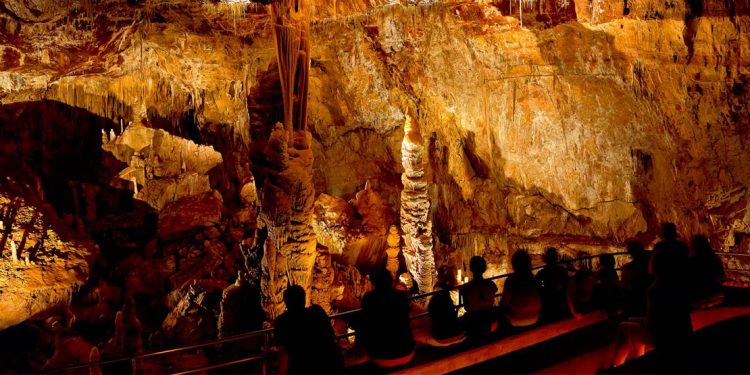

It’s inky black in here. All sense of proportion vanishes and the silence is broken only by distant trickling water. In the heavy humid air, I abandon any thoughts of a career in spelunking. A low spotlight relieves the darkness, illuminating a towering tangle of rocky arms and bulges and as I turn, a water droplet skims my cheek – a cave kiss.

This moist welcome is courtesy of Arizona’s newest State Park attraction, Kartchner Caverns. Their opening eagerly anticipated for years, the caves can now be toured in comfort along paved walkways with a guide, instead of on hands and knees across rubble as the caverns’ discoverers did.

In 1974 Randy Tufts and Gary Tenen found a small hole in the limestone hills at the base of the Whetstone Mountains, southeast of Tucson, Arizona. From it poured warm air reeking of bat guano — a sure sign of life underground, quite likely in a cave. Into the hole they slithered to find the spelunker’s ultimate dream – enormous, pristine caverns. Could you keep secret the most astounding discovery of your lifetime? For more than a week – a month – years?

They did. Having seen many vandalized and garbage-filled caves in their explorations and wanting better for their find, they took on the mantle of stewardship for it. They code named the cave Xanadu and kept it a secret as they explored its caverns and passageways

After four years of secrecy, the explorers finally told owners James and Lois Kartchner what lay beneath their land and enlisted their help in finding a way to protect the caverns. Concluding the best chance for their careful preservation was as a park, negotiations with the Nature Conservancy and the Arizona State Parks Board ensued. The public was let in on the secret of the newly purchased land and plans for a State Park in 1988 but it took more than a decade until the caverns could be toured.

The next eleven years were spent in careful preparation for opening the caves and every effort was made to minimize any detrimental effects of development. Huge double entry doors provide an airlock to prevent the drying effects of above ground desert air. The temperature is held constant at 68 degrees and the humidity at 98 percent. Walkways are dimly lit only when in use. Photography is not allowed and the guides continually admonish not to touch the cave walls.

On a mud flat only the footprints laid by Tufts and Tenen are visible and every subsequent worker or explorer conscientiously matches these. All work on the underground trails is done by hand with the necessary cement carried in buckets and rocks moved manually. Not only are the cave environment and its formations conscientiously protected, the cave’s bats are too.

During the summer months, over 1000 female cave myotis bats return to Kartchner Caverns and commandeer the “Big Room” for a nursery. They arrive in late April to raise their young and stay until mid-September when the pups reach migratory size. Bats act as a cave’s only living link with the outside world. Their deposits of guano, with scent strong enough to attract intrepid explorers, are essential to the cave’s food chain of fungi, bacteria, and insects. Preparation work on the caverns was closely monitored to ensure the bats were not disturbed

In November 1999, a full twenty-five years after Tufts and Tenen made the discovery of their lives, Kartchner Caverns State Park opened. At the moment, public tours start in the Discovery Center and go underground to the Throne and Rotunda Rooms. Each the size of a football field, these galleries are still-growing caves, filled with a kaleidoscope of colors and speleotherms of such variety they tantalize the imagination.

From little known locales to places that are making a comeback, these top travel destinations for 2019 will give you a year full of incredible experiences.

Speleotherms form ever so slowly over thousands of years. Water, seeping in from the surface, deposits dissolved calcite onto cave surfaces. The form a deposit eventually takes depends on whether the water flows, drips, condenses, or pools. Drips become stalactites, drawing infinitesimally closer to the stalagmites growing up to meet them. Where they have met, giant white columns stand stately.

Curtains of stalactites look like nasty teeth in an open jaw and butterscotch flowstone is a rich pool of caramel for dipping apples. Bizarrely intermingled rock arms and overflowing ice cream cones would inspire one of Geiger’s aliens. Creamy white shields glisten with water, the cave’s lifeblood, and aptly named bacon rock ripples in thin sheets of striated brown and white. The world’s second longest soda straw, a very fine, hollow stalactite, pierces through the darkness for over twenty-one feet.

The soda straw’s delicateness contrasts with Kubla Khan, the massive column at the center of the Throne Room. It is an imposing fifty-eight feet tall with flowstone draped in globs like a giant pot boiling over — no two sections are alike. As a light show highlights its architectural shapes, I imagine the awe Tufts and Tenen must have felt seeing it for the first time.

The lights fade and the darkness closes in. Our guide Pam bids us farewell with a quote from Samuel Taylor Coleridge “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan, a stately pleasure dome decree, where Alph, the sacred river ran through caverns measureless to man.”

If You Go

Kartchner Caverns State Park is approximately 265 kilometers southeast of Phoenix and 80 kilometers east of Tucson, near Benson, Tombstone, and Tubac.

For information, call 520 – 586 – 4100

The tour is approximate 60 minutes long, 45 of which is spent in the caverns.

Author

Karoline Cullen